At one time or another we have all suffered from obvious colour casts in our slides, colour casts caused by the ambient light not being 'neutral'. The problem is easy to cure using filters of various colours, but it is difficult to know which filter to use. With a colour analyser or colour temperature meter it becomes easy. We have taken a closer look at three different colour temperature meters on the market. The Minolta Color Meter IIIF is a clear improvement on the old Color Meter IIF. The Gossen Color Master 3F and Broncolor FCC are the other two. But before we take a closer look at these three meters and the differences between them, we shall go over how a colour temperature meter works, how to use it, and why we need to use one at all.

At one time or another we have all suffered from obvious colour casts in our slides, colour casts caused by the ambient light not being 'neutral'. The problem is easy to cure using filters of various colours, but it is difficult to know which filter to use. With a colour analyser or colour temperature meter it becomes easy. We have taken a closer look at three different colour temperature meters on the market. The Minolta Color Meter IIIF is a clear improvement on the old Color Meter IIF. The Gossen Color Master 3F and Broncolor FCC are the other two. But before we take a closer look at these three meters and the differences between them, we shall go over how a colour temperature meter works, how to use it, and why we need to use one at all.Take the lights temperature and avoid colour casts At one time or another we have all suffered from obvious colour casts in our slides, colour casts caused by the ambient light not being 'neutral'. The problem is easy to cure using filters of various colours, but it is difficult to know which filter to use. With a colour analyser or colour temperature meter it becomes easy. We have taken a closer look at three different colour temperature meters on the market. The Minolta Color Meter IIIF is a clear improvement on the old Color Meter IIF. The Gossen Color Master 3F and Broncolor FCC are the other two. But before we take a closer look at these three meters and the differences between them, we shall go over how a colour temperature meter works, how to use it, and why we need to use one at all.

|

Two scales Colour temperature meters analyse light in two ways. They measure the light source's colour temperature in Kelvin and suggest which filter should be used to compensate for any deviation from the colour temperature that the film is designed for. They also measure simple colour shifts towards green or magenta and suggest the appropriate magenta or green colour correction filter needed to correct the problem. In their instruction manual Minolta describe how their Color Meter IIIF measures light, and it is probable that the Gossen and Broncolor meters work along the same lines. Colour temperature meters react to light in the same way as colour film. Colour film has three layers that are sensitive to blue, green and red light (the three primary additive colours). Colour temperature meters for photographic use are therefore constructed to measure only blue, green and red light. It should be mentioned that there are also colour temperature meters that measure light in the same way that the eye perceives it, but these are less useful in photography. To decide upon a suitable filter, the meter compares the light's red content with its blue. Excessive blue means that the colour temperature is too high, and that a yellow or amber filter should be used to balance the light. The meter interprets excessive red to mean that the colour temperature is too low, and accordingly recommends the use of a blue filter. The meter readings are either shown on a colour temperature scale, expressed in Kelvin or as a deviation from 'normal' in Mired units (Mireds are explained later in the article), or a particular Wratten filter is recommended. To assess straightforward colour shifts and determine the colour correction filter that is needed, the meter compares the light source's red and green components. If the meter finds excessive red, it recommends that the photographer use a green filter of the appropriate density. If the green content is greater than the red, the meter suggests a magenta filter instead. Colour temperature Colour temperature is measured in Kelvin (K). Zero on the Kelvin scale is called 'absolute zero' and lies at -273 °C, but one degree Kelvin represents the same temperature change as one degree Celsius. Thus our zero degrees (0 °C) is the same as 273 K. As an ideal light source or 'blackbody' is heated its perceived colour changes, first to red, then yellow, then white and finally blue. The colour temperature of any arbitrary light source is determined by comparing its colour with that of an ideal blackbody; the colour temperature is the temperature in Kelvin at which the blackbody's colour matches that of the light source. Because reddish light has a low value on the Kelvin scale and bluish light a high one, so low colour temperatures give warm colours, while high colour temperatures give cold colours. At sunrise and sunset, when the sun is low, the colour temperature is low. 'Neutral' daylight has a colour temperature of about 5,500 K. This is the colour temperature for which normal daylight films are intended. Colour temperature is higher in the middle of the day, especially if you photograph in the shade and use light coming from the blue sky. In this case the colour temperature can be as high as 15,000 K. Different artificial light sources also have different colour temperatures. B-light (artificial or tungsten lighting) is about 3,200 K and is thus warmer in colour than neutral light. Kelvin and Mired The Kelvin scale can be translated into another scale that is more intuitive, the Mired scale (Micro Reciprocal Degrees), that avoids two drawbacks of the Kelvin scale. The first is the minor irritation that high colour temperatures give what we perceive as cold light while low temperatures give warm. The other problem with the Kelvin scale is that at high colour temperatures a change of 1,000 K is not as significant as at low colour temperatures. The difference between 3,000 K and 4,000 K is experienced as being much greater than that between 10,000 K and 11,000 K. Using the Mired scale the perceived difference is consistent over the entire length of the scale. The Mired value for a specific colour temperature is arrived at by multiplying the inverse of the value in Kelvin by 1,000,000. So if you divide 1,000,000 by the number of Kelvin you get the Mired value. Thus, for example, 1,000,000/5,500 = 182 Mired (M). Another unit used to measure colour temperature is the decaMired (dM). 1 dM is the same as 10 M. Colour balance filters To adjust for the colour temperature you use a filter in one of two colours; blue and amber. Blue filters raise the colour temperature while amber ones lower it. Kodak has a series of filters that are designed for this colour temperature adjustment. Wratten 81 and 85 filters in different strengths lower the colour temperature, while Wratten 82 and 80 raise it. Wratten filter names are not wholly logical. If we start with the blue filters, the palest coloured filter is called the Wratten 82. Then follow 82A, 82B, 82C, 80D, 80C, 80B and 80A. You can combine several filters of different strengths to achieve an even stronger blue, or to get finer subdivisions. For example, an 80D combined with an 82A gives a colour temperature difference that lies between 80D and 80C. If we go in the other direction, with amber filters, Kodak have chosen to label these with odd numbers. An 81 gives the smallest difference. Then follow in (or rather, out of) turn 81A, 81B, 81C, 81D, 81EF, 85C, 85 and 85B. Colour balance filters alter the colour temperature by a certain number of Mireds. These values are shown in the table. For example, an 81B filter lowers the colour temperature by about 27 M. A colour balance filter will also absorb some light, which means that the exposure has to be compensated to avoid underexposure. German filters German-made filters have their own classification system: KR and KB or CR and CB, where KR and CR are reddish, while KB and CB are blue. B+W call their filters KR and KB. The reds are KR1.5, KR3, KR6, KR12 and KR15, while the blues are KB1.5, KB3, KB6, KB12, KB15 and KB20. 1.5 is the weakest, 20 the strongest. The numbers are the dM-alteration of colour temperature. KB12 therefore changes the colour temperature by 12 dM towards blue, which is the same as 120 M, which in its turn means that it approximates a Wratten 80B filter that raises the colour temperature by about 112 M. In the table you can compare the different KB and KR filters with the Wratten filters. The Broncolor FCC and Minolta Color Meter IIIF can easily be used to give you the B+W KB and KR filter numbers. Simply add a decimal point to the Mired deviation given by the meter's light temperature reading, and you have the dM value (which in turn gives the KB and KR values). An example. The sun is low, and we want to take a picture that looks neutral in colour. We measure the colour temperature and read on the display that it is 3,460 K. This corresponds to a -107 M deviation from a neutral colour temperature (5,550 K), a difference that is also displayed on the meter. 107 M is the same as 10.7 dM, and because it is a negative Mired value we need to use a blue filter. A B+W KB10 is therefore the filter to use. Hasselblad call their filters CR and CB, but otherwise use the same classification scheme as B+W. Minolta, Gossen and Broncolor The three new colour temperature meters have many features in common. All meter normal light, flash, or a mixture of the two. The meters can be set for daylight film, and A- or B-balanced film for artificial light. On the Broncolor and Gossen meters you can fine tune the colour temperature settings. Minolta has developed this function even further with nine programmable channels for different purposes. For example, you can programme in specific values for the films you use frequently, so if the film itself needs to be filtered to ensure colour neutrality, this can be programmed in on one channel. You can also create settings for special conditions, for example for sunsets. When a 'sunset' picture is to be taken, you measure the colour temperature, and the meter automatically gives a filter recommendation to retain the desired mood. These adjustments can of course be made using the Broncolor and Gossen meters, but you have to note down the settings and programme them in on each separate occasion. Flash metering All three meters can also measure the colour temperature of flash and mixed light. The Color Meter IIIF is equipped with an exposure time scale so that the relative significance of normal light and flash can be varied. With longer shutter speeds the ambient light plays a bigger role in the exposure, and therefore we need more compensation for any imbalance in the light's colour. The meter automatically takes this into account, and the time can even be corrected after the measurement has been taken. On the Broncolor FCC you can only set two different times, 1/30 and 1/250 seconds. The Broncolor meter has a feature not shared by the others: it can measure the flash's duration. The display shows strobe times between 1/15 and 1/8,000 seconds. Powerful flash units at high power levels give surprisingly long burning times, something that can result in unexpected blurring when shooting moving subjects. These long times are revealed by the Broncolor FCC so that the photographer can exercise caution and avoid unintentional motion blur. Diverse meter readings Despite all the advanced modern electronics and apparently watertight theoretical models of metering and colour correction, these colour temperature meters have to be used with a healthy scepticism. They don't get it right in all situations. When using all three meters we occasionally got wildly varying results. In part this demonstrated the importance of the metering angle. In certain lighting situations we got significant deviations when using the same meter at different angles. It was also revealed that the three meters gave very different readings when measuring in the same light. Light from a cloudy sky gave 9,700 K with the Gossen, 8,000 K with the Broncolor, and 7,610 K with the Minolta. A picture that was fully corrected according to the Gossen meter would therefore have a significantly warmer colour than one corrected using the Minolta or Broncolor readings. In general the Gossen meter gave higher colour temperature readings than the other two. The only thing to do is to calibrate your meter before you can rely on it one hundred per cent. Take a series of test shots in different light, noting which correction filters you used. Judge the results on a light table that has the correct colour temperature. Learn how the meter measures in different lighting situations, and take note of the meter's particular quirks. Our trial shots showed that the Minolta and Broncolor overcompensated warm incandescent light - the pictures were too blue. Here the Gossen gave the correct compensation. In other situations we got more suitable values from the Minolta and Broncolor. In warm sunshine and blue shadow the results were clearer with the Minolta and Broncolor. In fluorescent lighting the Minolta's recommendation produced the best results. The Broncolor was a bit too warm and the Gossen much too warm. The Minolta meter is the easiest to use, with its display in Kelvin and Mireds deviation, Wratten colour balance filter numbers, and colour correction filter strengths. The Gossen does not have a Mired setting, and the Broncolor, with its clumpy design and small, badly organised buttons, gives a less pleasing impression. The Broncolor meter is also not really sensitive enough when measuring flash. |

|

| |

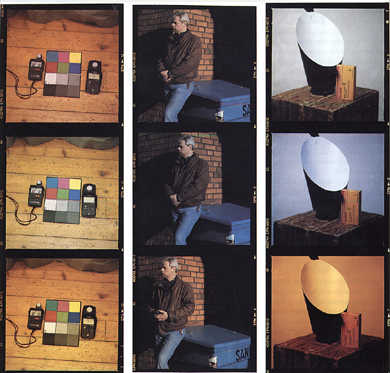

Left images (top to bottom: Gossen, Minolta, no filter) In fluorescent light colours become much too warm in tone, and have a definite green cast. Here the Minolta recommended 82A + 80C + 25M. The result is almost perfectly neutral. The exposure required a two-step compensation to prevent it from becoming too dark. With the Gossen's 80D + 30M recommendation and one-step compensation, we removed the green cast but the colours remained much too warm. The Broncolor came in between the Minolta and the Gossen. Center images Sunlight from a relatively low-lying winter sun has a low colour temperature. The Minolta reading was 4,000 K and the Gossen 4,750 K. The picture taken with Minolta's suggested correction (Wratten 82C) had the cleanest colours, but the Gossen picture (82A) would be more pleasing to many. The meters can also be used 'backwards' to add attractive colour casts to your pictures. Right images Incandescent light of about 3,500 K needs strong filtering. With the Gossen's recommendation of 80A + 80C + 5M the picture was completely neutral. The Minolta suggested a bluer filtration of 80A + 80B + 4M that gave a distinct blue cast to the picture. The table below A schematic comparison between types of ambient light, colour temperature (in Kelvin, Mireds, and deviation from daylight in Mireds), and Wratten, KB and KR filters. If the colour temperature is 10,000 K, and a daylight film is being used, an 85C filter should be used. If the colour temperature meter shows a deviation of 60 M, you should filter daylight film with an 80D or KB6 filter. |

||

| ||||